Work hardening

Work hardening, also known as strain hardening or cold working, is the strengthening of a metal by plastic deformation. This strengthening occurs because of dislocation movements within the crystal structure of the material.[1] Any material with a reasonably high melting point such as metals and alloys can be strengthened in this fashion. Alloys not amenable to heat treatment, including low-carbon steel, are often work-hardened. Some materials cannot be work-hardened at normal ambient temperatures, such as indium, however others can only be strengthened via work hardening, such as pure copper and aluminum.[2]

Work hardening may be desirable or undesirable depending on the context. An example of undesirable work hardening is during machining when early passes of a cutter inadvertently work-harden the workpiece surface, causing damage to the cutter during the later passes. An example of desirable work hardening is that which occurs in metalworking processes that intentionally induce plastic deformation to exact a shape change. These processes are known as cold working or cold forming processes. They are characterized by shaping the workpiece at a temperature below its recrystallization temperature, usually at the ambient temperature.[3] Cold forming techniques are usually classified into four major groups: squeezing, bending, drawing, and shearing. Examples of applications include the heading of bolts and cap screws and the finishing of cold rolled steel.

Contents |

History

Copper was the first metal in common use for tools and containers since it is one of the few metals available in non-oxidized form, not requiring the smelting of an ore. Copper is easily softened by heating and then cooling (it does not harden by quenching, as in cool water). In this annealed state it may then be hammered, stretched and otherwise formed, progressing toward the desired final shape, but becoming harder and less ductile as work progresses. If work continues beyond a certain hardness the metal will tend to fracture when worked and so it may be re-annealed periodically as the shape progresses. Annealing is stopped when the workpiece is near its final desired shape, and so the final product will have a desired stiffness and hardness. The technique of repoussé exploits these properties of copper, enabling the construction of durable jewelry articles and sculptures (including the Statue of Liberty).

For metal objects designed to flex, such as springs, specialized alloys are usually employed in order to avoid work hardening (a result of plastic deformation) and metal fatigue, with specific heat treatments required to obtain the necessary characteristics.

Devices made from aluminum and its alloys, such as aircraft, must be carefully designed to minimize or evenly distribute flexure, which can lead to work hardening and in turn stress cracking, possibly causing catastrophic failure. For this reason modern aluminum aircraft will have an imposed working lifetime (dependent upon the type of loads encountered), after which the aircraft must be retired.

Theory

Before work hardening, the lattice of the material exhibits a regular, nearly defect-free pattern (almost no dislocations). The defect-free lattice can be created or restored at any time by annealing. As the material is work hardened it becomes increasingly saturated with new dislocations, and more dislocations are prevented from nucleating (a resistance to dislocation-formation develops). This resistance to dislocation-formation manifests itself as a resistance to plastic deformation; hence, the observed strengthening.

In metallic crystals, irreversible deformation is usually carried out on a microscopic scale by defects called dislocations, which are created by fluctuations in local stress fields within the material culminating in a lattice rearrangement as the dislocations propagate through the lattice. At normal temperatures the dislocations are not annihilated by annealing. Instead, the dislocations accumulate, interact with one another, and serve as pinning points or obstacles that significantly impede their motion. This leads to an increase in the yield strength of the material and a subsequent decrease in ductility.

Such deformation increases the concentration of dislocations which may subsequently form low-angle grain boundaries surrounding sub-grains. Cold working generally results in a higher yield strength as a result of the increased number of dislocations and the Hall-Petch effect of the sub-grains, and a decrease in ductility. The effects of cold working may be reversed by annealing the material at high temperatures where recovery and recrystallization reduce the dislocation density.

A material's work hardenability can be predicted by analyzing a stress-strain curve, or studied in context by performing hardness tests before and after a process.

Elastic and plastic deformation

Work hardening is a consequence of plastic deformation, a permanent change in shape. This is distinct from elastic deformation, which is reversible. Most materials do not exhibit only one or the other, but rather a combination of the two. The following discussion mostly applies to metals, especially steels, which are well studied. Work hardening occurs most notably for ductile materials such as metals. Ductility is the ability of a material to undergo large plastic deformations before fracture (for example, bending a steel rod until it finally breaks).

The tensile test is widely used to study deformation mechanisms. This is because under compression, most materials will experience trivial (lattice mismatch) and non-trivial (buckling) events before plastic deformation or fracture occur. Hence the intermediate processes that occur to the material under uniaxial compression before the incidence of plastic deformation make the compressive test fraught with difficulties.

A material generally deforms elastically if it is under the influence of small forces, allowing the material to readily return to its original shape when the deforming force is removed. This phenomenon is called elastic deformation. This behavior in materials is described by Hooke's Law. Materials behave elastically until the deforming force increases beyond the elastic limit, also known as the yield stress. At this point, the material is rendered permanently deformed and fails to return to its original shape when the force is removed. This phenomenon is called plastic deformation. For example, if one stretches a coil spring up to a certain point, it will return to its original shape, but once it is stretched beyond the elastic limit, it will remain deformed and won't return to its original state.

Elastic deformation stretches atomic bonds in the material away from their equilibrium radius of separation of a bond, without applying enough energy to break the inter-atomic bonds. Plastic deformation, on the other hand, breaks inter-atomic bonds, and involves the rearrangement of atoms in a solid material.

Dislocations and lattice strain fields

In materials science parlance, dislocations are defined as line defects in a material's crystal structure. They are surrounded by relatively strained (and weaker) bonds than the bonds between the constituents of the regular crystal lattice. This explains why these bonds break first during plastic deformation. Like any thermodynamic system, the crystals tend to lower their energy through bond formation between constituents of the crystal. Thus the dislocations interact with one another and the atoms of the crystal. This results in a lower but energetically favorable energy conformation of the crystal. Dislocations are a "negative-entity" in that they do not exist: they are merely vacancies in the host medium which does exist. As such, the material itself does not move much. To a much greater extent visible "motion" is movement in a bonding pattern of largely stationary atoms.

The strained bonds around a dislocation are characterized by lattice strain fields. For example, there are compressively strained bonds directly next to an edge dislocation and tensilely strained bonds beyond the end of an edge dislocation. These form compressive strain fields and tensile strain fields, respectively. Strain fields are analogous to electric fields in certain ways. Additionally, the strain fields of dislocations, obey the laws of attraction and repulsion.

The visible (macroscopic) results of plastic deformation are the result of microscopic dislocation motion. For example, the stretching of a steel rod in a tensile tester is accommodated through dislocation motion on the atomic scale.

Increase of dislocations and work hardening

Increase in the number of dislocations is a quantification of work hardening. Plastic deformation occurs as a consequence of work being done on a material; energy is added to the material. In addition, the energy is almost always applied fast enough and in large enough magnitude to not only move existing dislocations, but also to produce a great number of new dislocations by jarring or working the material sufficiently enough. New dislocations are generated in proximity to a Frank-Read source.

Yield strength is increased in a cold-worked material. Using lattice strain fields, it can be shown that an environment filled with dislocations will hinder the movement of any one dislocation. Because dislocation motion is hindered, plastic deformation cannot occur at normal stresses. Upon application of stresses just beyond the yield strength of the non-cold-worked material, a cold-worked material will continue to deform using the only mechanism available: elastic deformation, the regular scheme of stretching or compressing of electrical bonds (without dislocation motion) continues to occur, and the modulus of elasticity is unchanged. Eventually the stress is great enough to overcome the strain-field interactions and plastic deformation resumes.

However, ductility of a work-hardened material is decreased. Ductility is the extent to which a material can undergo plastic deformation, that is, it is how far a material can be plastically deformed before fracture. A cold-worked material is, in effect, a normal (brittle) material that has already been extended through part of its allowed plastic deformation. If dislocation motion and plastic deformation have been hindered enough by dislocation accumulation, and stretching of electronic bonds and elastic deformation have reached their limit, a third mode of deformation occurs: fracture.

Quantification of work hardening

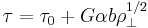

The stress,  , of dislocation is dependent on the shear modulus, G, the magnitude of the Burgers vector, b, and the dislocation density,

, of dislocation is dependent on the shear modulus, G, the magnitude of the Burgers vector, b, and the dislocation density,  :

:

where  is the intrinsic strength of the material with low dislocation density and

is the intrinsic strength of the material with low dislocation density and  is a correction factor specific to the material.

is a correction factor specific to the material.

As shown in Figure 1 and the equation above, work hardening has a half root dependency on the number of dislocations. The material exhibits high strength if there are either high levels of dislocations (greater than 1014 dislocations per m2) or no dislocations. A moderate number of dislocations (between 107 and 109 dislocations per m2) typically results in low strength.

Example

For an extreme example, in a tensile test a bar of steel is strained to just before the distance at which it usually fractures. The load is released smoothly and the material relieves some of its strain by decreasing in length. The decrease in length is called the elastic recovery, and the end result is a work-hardened steel bar. The fraction of length recovered (length recovered/original length) is equal to the yield-stress divided by the modulus of elasticity. (Here we discuss true stress in order to account for the drastic decrease in diameter in this tensile test.) The length recovered after removing a load from a material just before it breaks is equal to the length recovered after removing a load just before it enters plastic deformation.

The work-hardened steel bar has a large enough number of dislocations that the strain field interaction prevents all plastic deformation. Subsequent deformation requires a stress that varies linearly with the strain observed, the slope of the graph of stress vs. strain is the modulus of elasticity, as usual.

The work-hardened steel bar fractures when the applied stress exceeds the usual fracture stress and the strain exceeds usual fracture strain. This may be considered to be the elastic limit and the yield stress is now equal to the fracture toughness, which is of course, much higher than a non-work-hardened-steel yield stress.

The amount of plastic deformation possible is zero, which is obviously less than the amount of plastic deformation possible for a non-work-hardened material. Thus, the ductility of the cold-worked bar is reduced.

Substantial and prolonged cavitation can also produce strain hardening.

Additionally, jewelers will construct structurally sound rings and other wearable objects (especially those worn on the hands) that require much more durability (than earrings for example) by utilizing a material's ability to be work hardened. While casting rings is done for a number of economical reasons (saving a great deal of time and cost of labor), a master jeweler may utilize the ability of a material to be work hardened and apply some combination of cold forming techniques during the production of a piece.

Empirical relations

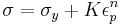

There are two common mathematical descriptions of the work hardening phenomenon. Hollomon's equation is a power law relationship between the stress and the amount of plastic strain:

where σ is the stress, K is the strength index, εp is the plastic strain and n is the strain hardening exponent. Ludwik's equation is similar but includes the yield stress:

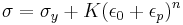

If a material has been subjected to prior deformation (at low temperature) then the yield stress will be increased by a factor depending on the amount of prior plastic strain ε0:

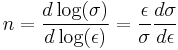

The constant K is structure dependent and is influenced by processing while n is a material property normally lying in the range 0.2–0.5. The strain hardening index can be described by:

This equation can be evaluated from the slope of a log(σ) - log(ε) plot. Rearranging allows a determination of the rate of strain hardening at a given stress and strain:

Processes

The following is a list of cold forming processes:[4]

- Squeezing

- Bending

- Angle bending

- Roll bending

- Draw and compression

- Roll forming

- Seaming

- Flanging

- Straightening

- Shearing

- Drawing

- Tube drawing

- Wire drawing

- Spinning

- Embossing

- Stretch forming

- Sheet metal drawing

- Ironing

- Superplastic forming

Techniques have been designed to maintain the general shape of the workpiece during work hardening, including shot peening and equal channel angular extrusion.

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages:[3]

- No heating required

- Better surface finish

- Superior dimensional control

- Better reproducibility and interchangeability

- Directional properties can be imparted into the metal

- Contamination problems are minimized

The increase in strength due to strain hardening is comparable to that of heat treating. Therefore, it is sometimes more economical to cold work a less costly and weaker metal than to hot work a more expensive metal that can be heat treated, especially if precision or a fine surface finish is required as well. The cold working process also reduces waste as compared to machining, or even eliminates with near net shape methods.[3] The material savings becomes even more significant at larger volumes, and even more so when using expensive materials, such as copper. The saving on raw material as a result of cold forming can be very significant, as is saving machining time. Production cycle times when cold working are very short. On multi-station machinery, production cycle times are even less. This can be very advantageous for large production runs.

During cold working the part undergoes work hardening and the microstructure deforms to follow the contours of the part surface. Unlike hot working, the inclusions and grains distort to follow the contour of the surface, resulting in anisotropic engineering properties.[5]

Disadvantages:[3]

- Greater forces are required

- Heavier and more powerful equipment and stronger tooling are required

- Metal is less ductile

- Metal surfaces must be clean and scale-free

- Intermediate anneals may be required to compensate for loss of ductility that accompanies strain hardening

- The imparted directional properties may be detrimental

- Undesirable residual stress may be produced

Due to the large capital costs required to set up a cold working process the process is usually only suitable for large volume productions.[3]

Intermediate annealings may be required to reach the required ductility to continue cold working a workpiece, otherwise it may fracture if the ultimate tensile strength is exceeded. An anneal may also be used to obtain the proper engineering properties required in the final workpiece. Also, the distorted grain structure that gives the workpiece its superior strength can lead to residual stresses.[5]

Cold worked items suffer from a phenomenon known as springback, or elastic springback. After the deforming force is removed from the workpiece, the workpiece springs back slightly. The amount a material springs back is equal to Young's modulus for the material from the final stress.[6]

References

- ^ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 60.

- ^ Smith & Hashemi 2006, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d e Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 375.

- ^ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 408.

- ^ a b Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 378.

- ^ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 376.

Bibliography

- Degarmo, E. Paul; Black, J T.; Kohser, Ronald A. (2003), Materials and Processes in Manufacturing (9th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-65653-4.

- Smith, William F.; Hashemi, Javad (2006), Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering (4th ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-295358-6.